Title: The Floodgates of Anarchy

Date: 1970

Topics: anarchism

Source: Retrieved on July 8, 2012 from libcom.orgStuart Christie, Albert Meltzer

The Floodgates of Anarchy

The Floodgates of Anarchy — Stuart Christie and Albert Meltzer

Publisher’s note to the 1998 electronic edition

1 The Class Struggle and Liberty

4 Social Protest and a New Class

The Floodgates of Anarchy — Stuart Christie and Albert Meltzer

This polemic approaches the subject of anarchism in relation to class struggle. It presents an argument against class-based society and hierarchy and advocates for a free and equal society based on individual dignity and merit.

Drawing from the authors’ experiences as activists and documenting the activities of other 20th-century anarchists—including clandestine activities and social change by any means—this fundamental text asserts that government is the true enemy of the people and that only through the dissolution of government can the people put an end to exploitation and war, leading to a fully free society. This is the 1970 edition.

Publisher’s note to the 1998 electronic edition

We have three good reasons for reissuing this book. First, it was written in the aftermath of the heady events of 1967 and 1968, so that in some sense it completes its third decade of existence this year. If nothing else it is a witness to its time-indeed the dated or obscure references in the text are proof of just that!

Also, Albert is no longer with us in person, and that is sad. A meeting with Albert was a true encounter. He always gave cheer. His obstinacy was never more than caution. His ever-present dedication, common sense, erudition, seriousness and wit were a delight. Luckily for us, they spring from every page of this book, even those that did not come principally from his typewriter.

Lastly, there still remain hardly any books on the subject of anarchism in relation to the class struggle. Yet with very few exceptions every human being born must fight for survival and dignity from the moment they first draw breath-or someone must do it for them. Even the fortunate few are affected by the plight of the dispossessed masses, living as they do behind the thick skins and the high walls that they need to safeguard their privileges. Since this book was written, those skins may or may not have got thicker, those walls higher. For sure, though, the gap between rich and poor has widened noticeably everywhere. If the ground that has been so lost is ever to be regained, it will only be so when the poor fight back. This book is, we hope, part of that fight.

“What causes war is the meekness of the many,” the authors write. Just so. It is the cause, too, of every disaster that befalls the many who are dispossessed. And what causes that meekness is largely the failure of those many to recognise the force within themselves that is the potential to combine to win a better world-by opening “the floodgates of anarchy”.

Preface

Writing on the subject of anarchism in relation to the class struggle we had few, if any, books to consult, despite the writings of earlier anarchists when class divisions were taken for granted and before the development of current social and economic trends. The anarchist movement owes little to the writings of the “intellectual”-on the contrary, professional writers have dipped into the achievements of anarchist workers to enlighten themselves on social theory or to formulate other theories.

I was helped in my early thoughts by coming from Glasgow and Blantyre where I grew up amongst miners and others who had kept the socialist and libertarian tradition alive for more than sixty years. I subsequently had the advantage of holding discussions with comrades of the clandestine struggle against Franco such as Octavio Alberola; Salvador Gurruchari and Jose Pascual Palacios. I must also add to this list Luis Andres Edo and Alain Pecunia, a fellow prisoner in Carabanchel, Madrid, Prison. Without them and people like them we would have been gobbled up or annihilated entirely by the machinery of the State.

I may say that this book would never have appeared without the help of my co-author Albert Meltzer, a veteran of the anarchist movement for over a third of a century. Albert has worked with stalwarts of a previous generation of British anarchists-Mat Kavanagh, Frank Leech, Albert Grace, Sam Mainwaring Jnr, and others-as well as collaborating with revolutionaries in Asia and Europe. Our work in the Anarchist Black Cross, an organisation for helping prisoners and activists abroad and in Britain, resulted in this book.

STUART CHRISTIE

The major battles that we fought in the past were under the red flag of socialism and working class collectivism. The life’s blood of anarchists, too, “dyed its every fold”. These colours, together with the battle honours and passwords, have been captured by the enemy. They are now used with intent to deceive.

The classic books about anarchism were written under the red banners. For then socialism had to do with the abolition of exploitation and the establishment of both freedom and equality. The black banners were raised only to call for greater militancy in achieving that goal. In countries such as Russia and Italy, the totalitarian victory was resisted to the bitter end.

The red-and-black banner was first raised in Spain, where the labour movement and anarchism had not parted company, and were almost synonymous. Little has been written on anarchism in relation to the class struggle, and nothing at all (so far as I can discover) in English. The present book is one of the few contemporary writings on what anarchists think, as distinct from academic interpretations as to what they ought to think.

Amongst others I should like to thank Ted Kavanagh for many helpful discussions.

ALBERT MELTZER

Introduction

The end of the First World War saw the growth of super-government. Capitalism, trying to escape the consequences of war, lost its liberal facade. In some cases it had to yield completely to State control, masquerading as communism-which had abolished the old ruling class only to create a new, based not upon profit but upon privilege. In other cases it injected itself with a shot of the same drug, and the nightmare world of fascism was a trip into darkness. The side effect of these experiences was to heighten appreciation of the older form of capitalism. Surely, many argued, the liberal and democratic form of government that capitalism used to provide, and could do so no longer, was a lesser evil? The argument is strangely archaic now, when the growth of the Destruction State means that it is of little significance whether the leadership is bland or brutal; whether it enforces its decisions by unarmed policemen directing protest marchers down empty streets, or turns out the tanks and tear-gas upon them. The issues that are involved today are so vital to the very continuance of mankind that it renders insignificant the fact of whether the maniacs in charge of our destiny come to power via smoke-filled backrooms or by a “whiff of grapeshot”.

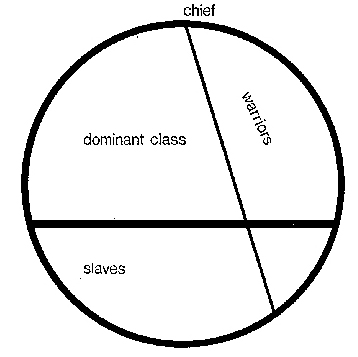

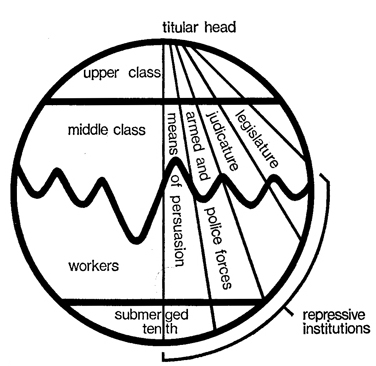

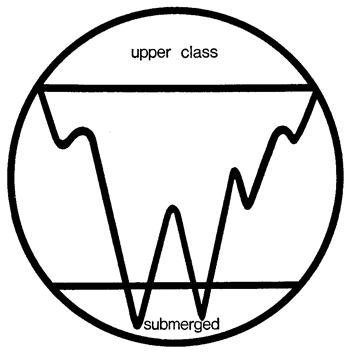

The State is very clearly our enemy; if we do not destroy it first, it will destroy us. There will be no more national wars on a world-wide scale, or at least, not for long — power-mad clashes will lead to instant destruction. The front-line of the future will confront us and them. Who are “they” and who are “us”? It may be difficult to define, although we all feel it instinctively. They are the dominant class, and those associated with power. We are those who are expected to be the pawns of power. They are the dominant class, we are the subjects. They are the aggressors, but our initiatives to overthrow them are condemned as disturbing the peace. They are the conquerors and we are the conquered, and the failure to define is the result of grass growing over the battlefields. Provided we conform, or try to assimilate, they are content to leave us alone; but even so, they cannot leave the world alone. Those associated with power make their own plans for survival in the event of nuclear war; they may even dream that there are other worlds for them to conquer. To keep us quiet they gloss over the differences within society, and to such an extent that we can hardly tell at times where the division comes. That is the success of the means of persuasion by which, among other instruments of oppression, they exploit us.

One may isolate a section of the ruling class and attack it; but essentially the enemy of man is the means by which he is governed. It is an impersonal instrument although manned by real people. So far back as the ancient Chinese philosophers, it was held that man could not be expected to revere that by which he was chastised and the symbol by which he was made subject (a reasonable expectation later nullified by the Christian church). It was axiomatic to them that the man who sold out to government did so for unworthy reasons. Invited by the emperor to help him rule, one sage asked to be allowed to wash his ears; he was admonished by another sage not to let his oxen drink from the water in which he bathed the ears that had listened to such a proposal.

How can there be antagonism between man and a man-made institution? Because it marks the division of man into rulers and ruled. Is government not merely the administration of society? Yes, but against its will. Society is necessary to unite us; the State, which comes into being to dominate, divides us. Are governments not merely composed of human beings, with all their faults and virtues? Yes, but in order to oppress their fellows. Humanity began with the fact of speech; society began with the art of conversation; the State began with a command.

Government represents the fetters upon society; even at its freest, it merely marks the point beyond which liberty may not go. The State is the preservation of class divisions, and if in that capacity it protects property, it does so in order to defend the interests of a governing class. While this may also entail preserving the lesser property rights of the lower class, at any rate from some inroads, this is merely done to strengthen respect for property. In a society where profit is not the motive, and the class divisions do not determine the economy, the State defends the interests of the bureaucracy.

Even those most concerned with the preservation of a governmental society-the propertied bourgeoisie-are constrained to admit that they do not inevitably get the best of the bargain. The prosperous citizen, with every conceivable need of government on the repressive side, is the more inclined to attack government taking over any other role than that of defending property or curbing working-class activity. Enthralled as he is with the notion of business reciprocity as ethics, he pays his taxes least willingly of all his commitments and sees no dishonour in cheating; everywhere else, even in his gambling debts, he sees the possibility of something for something, but from the State, nothing.

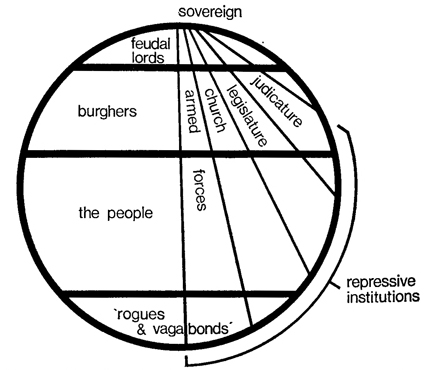

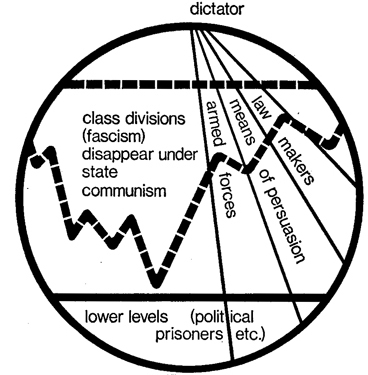

The State is a parasite upon society. It is ineradicable in a class-divided society, despite the hopes of early liberal capitalists and individualistic philosophers, because the protection of property divisions depends upon organised repression. Once any form of organised repression becomes stronger than any existing form of organised repression, it will take over the functions of the State. Marx (i)[1] analysed the structure of capitalism clearly enough to perceive that when the necessity for class division was no longer there those repressive institutions necessary for class rule would disappear. In the communist countries, however, it can be seen how the retention of other repressive organs of the State has meant that far from the State being abolished, it has been strengthened. It has combined the exploitative nature of capitalism with the ordinary repressive nature of the State, and made the latter a greater monstrosity than ever.

The American oil baron, who sneers at any form of State intervention in his manner of conducting business — that is to say, of exploiting man and nature — is also able to “abolish the State” to a certain extent. But he has to build up a repressive machine of his own (an army of sheriffs to guard his interests) and takes over as far as he can, those functions normally exercised by the government, excluding any tendency of the latter that might be an obstacle to his pursuit of wealth. The underworld of Cosa Nostra has, particularly in Sicily and the USA, built up a State within a State. Granted the necessity for protection from that threat which the Mafia itself presents, it affords as good a bargain as that provided by the State. Were it not there, no necessity for protection would arise. Were the State not there, no necessity for legal curbs would arise either. There would be no need for constitutional brakes upon power if the people were free.

In the rise of a gangster class, one sees the functions of the State at its crudest. It began “with the crack of the slave driver’s whip”. It reaches its highest point when it becomes not just the police contractor for the conqueror, but a ruling class in its own right. At that point — and this is sometimes heralded as socialism of the authoritarian type, though it is only done under that banner and could as well be the logical development of capitalism or of fascism — the bureaucrats take over the ministries and the accountants take over the industry. The State becomes not a mere committee for the propertied class, nor even the expression of a dictatorial caste, but a machine perpetuating rule for its own sake and for the aggrandisement of those comprising it. But it is ultimately doomed. The massive concentration of power in a scientific age means the decisions of universal life and death fall into the hands of a few people, accustomed to taking huge responsibilities upon themselves. They cannot imagine that their decisions are not sound ones. They have in their hands the ability to destroy society, and this they will do unless society destroys the State. If the State prevails, the world is doomed. The State being a parasite, it cannot live after it has killed the body on which it feeds.

Like the Great Pyramid, the State was built to the cult of slavery and survives to the cult of death. It has lost all responsibility to mankind; it has lost identity with individual persons and represents a faceless enemy. But it is not abuse of State authority that has occasioned this. It is the natural process of maintaining, through the years, division between conquered and conqueror. Civil war is latent in all imposed cultures. The forces of persuasion have blurred the outline of the struggle, but only the conception of the class-war makes sense of the economic conflicts in society.

It is no longer fashionable to harp upon class distinctions. Speaking of social change it is said that the “working class no longer exists”. Only when legislation is planned curbing what are alleged to be the malpractices of one class rather than those of another do we find that it is not quite true that “we are all workers now”!

The struggle for class and self-liberation is not to be compared with national conflicts. It is the function of the impersonal State to squander lives in war, or of a superior class to regard lesser humans as expendable; thus any war of the nation-state must in itself be in the nature of an atrocity. This need not be the case in the revolutionary process of breaking down the State, unless intolerable oppression has made people reckless of their own lives and determined to take vengeance (as in Spain in 1936). Those engaged in the struggle for a free society are usually, for that very reason, capable of a heightened appreciation of the condition of others. In any case, their enemies are not whole nations but individuals.

Yet, compared with other conflicts, social liberation is the most difficult of all to achieve, beside which national liberation is a divertissement. For class struggle implies not merely collective action but the breaking down of that sequence of events ingrained in our society as command-and-obey. Any form of social protest may be useful as an attempt to destroy this sequence, which saps the lifeblood of mankind and makes it possible for the few to govern the many.

Why, since people must outnumber the minority that comprises the State and its oppressive forces, have they submitted so meekly to it? Why do they quietly queue up to receive their marching orders to war, or to pay their taxes, or to be sentenced to death or forced labour? Society first submitted to the whip-to the armed forces in time of conquest, replaced in a stable society by the police force (or in a less stable society by the army in a police role). Primarily the police force is a method of political repression. Only secondarily is it the means by which, within the legal system, crimes against society are institutionalised by the legalisation of some and the outlawry of others. The outlawry of some crimes is, of course, useful if people have lost the initiative to put down antisocial behaviour themselves. This is the aspect of police work used to justify the whole. While it has a degree of inevitability in a State-ruled society, it also has an atrophying effect upon people’s initiative to deal with offences against society, and encourages the delinquency it professes to put down.

Since in the long run rule must be by consent, there is in addition to rule by the whip an apparatus of rule by persuasion, by brainwashing and mental conditioning and the whole process of education. It reaches the point where the British people, for instance, might even accept a Gestapo, provided it helped find their lost cats and assisted old ladies across the road.

True education began with an enquiring look; State education began with a salute. The building of a code of ethics and morals suitable for a servile people and adapted to the then current economic system, was originally entrusted to the priesthood, and a church was erected upon the need to subordinate mysticism to power, and to justify the actions of the ruling class. The process of persuasion is much more than the education which conditions the mind to receive it, and runs the whole gambit of national mystique. Education has long since ceased to be the monopoly of the Church, except in isolated corners of the world. In place of the religious organisation at the service of the State, and sometimes becoming a parallel State or even master of the secular State, there has been built, in palpable imitation in the totalitarian countries, a hegemonic party in charge of the holy truths (economic or social) that make the system tick. The totalitarian party system comes closer to the old Church, but has no difference with the multiple process nicknamed “the Establishment” in countries where there is a diversification of power, and the latter may contain many parties and conflicting interests within the one “Church”.

The old Church, and these neo-Churches, may be States within States, super-States, even supra-national States. Their reaction to the State itself, and their inter-reaction to each other, is the essence of what passes off as politics. Their quarrels may become tensions and even wars. These wars may even sometimes follow the lines of the class-war, which has driven its furrow through society, but do not produce victories or defeats for the working class, only disasters. Divisions out of time may be preserved, as papal rule petrified the Holy Roman Empire long after its decease. Countries such as Spain still preserve, like dinosaurs in ice, an aristocracy and feudal class fighting against encroaching capitalism.

Similarly, Judaeo-Christian morality has been preserved out of time, though suitably modified to conform to the penal code or business habits. (A notable exception is of course the injunction to the children of light to emulate the practice of fraudulent disposition whilst bailee. Luke 16. The Bible-worshipping judge of today, who loves money quite as much as any Pharisee, would be equally severe upon this-but it is, sigh the scholars, a difficult passage to translate.) In the main theologians have managed to reconcile Biblical morals with a society that outrages natural justice and propriety, and substitutes property laws. They are thus able to invoke divinity as idealised authority, which is why Bakunin (ii) said that “If God existed, it would be necessary to destroy him”.

The nation-state, from being a burden upon society, is elevated by idealistic conceptions-that it derives from God, or alternatively that it derives from necessity-and duties to it are shown as being “in the natural order of things”. The cult of nationalism derives from the need to bolster up the sense of duty to the State, just as does established religion. The nation-state is idealised by nationalism, and is shown in a favourable light against other nation-states. This nationalism is an invented ideal supplementing or substituting for religious (or neo-religious, i.e. party or Establishment) ideals. It is to mask the unloved and unlovable abstraction of the State with the idealised family of the race or nation.

The feeling of superiority that might be felt for one race over another for historic or purely fictitious reasons, or the inferiority felt (usually for economic reasons) is deliberately confused with one’s natural inclination for the people or places one knows best. It is institutionalised into a cult, not merely of nationalism but of a State.

Nationalism is an artificial emotion. It clings around the State like ivy, a parasite upon a parasite. Without a State to twine round, nationalism withers; language becomes dialect, and nationality becomes provincialism, for nationalism is a creature of power. Racialism, not in its usual journalistic sense but the folklore and ethnic traditions of particular peoples, is a plant of hardier growth, and flourishes unless the State takes positive measures to cut it down.

Whereas the creation of a multi-racial or supra-national State leads to an empire (super-State), reaction to it on the purely idealistic ground of race, nation, or difference in religion, is bound to be progressive. It helps to whittle away the bulwark of the State and breaks up the sequence of command-and-obey; but it is only progressive while it is unsuccessful. Hope is said to be a good breakfast but a poor supper. So is the struggle for national independence. The nationalist forms a new State but continues old forms of economic exploitation. By obtaining popular consent to the forms of rule, the new State legitimises oppression. However, the spirit of rebellion often persists even when nationalism triumphant has taken its dreary course.

All forms of economic exploitation arise from the division between classes and the fact that man is robbed of the full value of his labour. The monetary system is not a mere form of exchange, nor is it properly a science, but a fraud perpetuated by the State in order to legitimise poverty. Capitalist economics is a mystique rather than a science. The science called economics or political economy, wrote Herbert Read (iii)[2], “is the disgrace of a technological civilisation. It has failed to produce any coherent science of the production, distribution and consumption of the commodities proliferated by machine production. It has failed to give us an international medium of exchange exempt from the fluctuations and disasters of the gold standard. It is split into a riot of rival sects and irreconcilable dogmas which can only be compared to the scholastic bickerings of the Middle Ages.”

Stripped of its bare essentials and uncovered of its ideals — “We have another word for ideals — lies,” said Ibsen (iv) — political economy is an apology for civil war, in which one class has economic and political power and the other class is subject. If the latter revolts, it must fight. Since it has submitted and has been mentally processed, collectively and individually, there is some blurring of the division, and an escape clause is granted by which the occasional individual can transcend class barriers and be accepted on the other side. Hence the natural desire for self-betterment is distorted and it is made to appear that one’s position in society is the test of one’s abilities rather than of one’s exploitative value or sheer good luck.

Division is dreaded by the conservative-minded and is equated by them with the fratricidal struggles of the nation-state rather than with the age-old task of trying to get rid of oppressive institutions. For centuries the people have tried non-violent resistance — or “dumb insolence” as the army phrased it. (Manipulated enthusiastic participation is a modem invention, though it was implicit in the “bread and circuses” of old Rome.) But non-violent resistance is not enough. It has no lasting effect even when it becomes armed. A liberal with a gun is still only a liberal. Resistance is a beginning, but it is not enough. All it can do is to break down the sequence of command and obey. But resistance only becomes effective when it leads to that breakdown of authority, feared by the authoritarian, which is deliberately confused with the breakdown of all order.

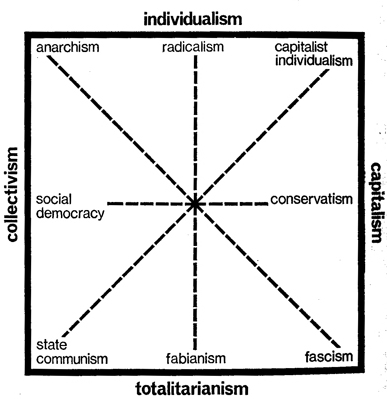

It is with this supposition — that the rule of law prevents disorder — that the revolutionary libertarian quarrels, and this is why he is branded as an anarchist. The anarchist believes that the absence of government (anarchy) is freedom. The non-anarchist supposes that the absence of government leads to innumerable disorders normally associated with weak or divided government, where there are the same evils as in strong government, but an absence of unified restraint.

Revolutionary anarchism is not something apart from the working-class struggle. In defining a labour movement, we see no liberty where there is exploitation and no socialism where liberty is lacking. We are for equality without bureaucracy, and for a victory of the masses without any ruling faction, old or new.

The generous-minded of the younger generation of the bourgeoisie are apparently more inclined to be with us than against us; they may exercise their right to secede from the rat race and renounce their privileges of birth or connected wealth. We ourselves had nothing to renounce but the illusions of duty with which man has been shackled.

If nowadays we have a little more to lose than mere chains, so much the more reason for making sure of victory. Should the ruling class find it necessary to make a fresh conquest over their subjects (as in Spain), they will take away even that little which we have.

1 The Class Struggle and Liberty

The theories of social revolution have not been produced by theorists, who at most have supplied the technical terms, often at the expense of these becoming looked on as clichés rather than as natural truths. Peter Kropotkin (v) is usually regarded as the main theoretician of anarchism, but he himself wrote upon the subject: “... if some of us have contributed to some extent to the work of liberation of exploited mankind, it is because our ideas have been more or less the expression of the ideas that are germinating in the very depths of the masses of the people. The more I live, the more I am convinced that no truthful and useful social science, and no useful and truthful social action, is possible but the science which bases its conclusions, and the action which bases its acts, upon the thoughts and inspirations of the masses. All sociological classes and all social actions which do not do that must remain sterile.”[3]

The fashionable philosophers of today, whose academic pedantry and class prejudices do not permit them to take note of anybody not mentioned in the university curriculum, will deny that such ideas germinate in the masses and will credit the motivation for social progress to classes of society more congenial to themselves.

It is by no means new to try to reconcile anarchism in terms of Marxism, as is done in the “student debate” of today. Even during the lifetime of Marx, the validity of his economic criticism of capitalism was accepted by the libertarian wing of the International (vi). The International was the first attempt to express the class struggle in terms of an organisation based upon the working class. The difference of thinking, as between Marxists and Bakuninists, was a clash between centralism and federalism, and on whether the existing State machinery should be used or destroyed. It is impossible to discuss the capitalist system in terms of changing it without some reference to the work of Marx, and some use of what have now become his clichés, even though the latter have often been used out of context to justify completely different concepts from those intended.

Perhaps to avoid the repeated use of the political cliché we need the skill of the Victorian telegraphist, accustomed to whittle down to two or three words the verbose lucubrations of the bourgeoisie. There is a classical story that, on one occasion during the Crimean War, a general sent a telegram urging that Lieutenant Dowbotham be granted every facility to prove his merits, and that consistent with his military duties it should be borne in mind that his advancement and protection would greatly please those distinguished persons vouching for him. In telegraphese this became “Look after Dowb”. So far as modern Britain is concerned, there is no need to think in terms of a conspiracy by the upper classes. Their watchword is still “Look after Dowb”. Those who feel that in persisting in using the phrase “class struggle” we are being unutterably banal might reflect on how upper-class endeavours are geared to looking after Dowb. He is guarded if not from the cradle, certainly from the classroom, until the grave (and beyond as far as the bourgeois historian is concerned).

To look after Dowb from his earliest induction in the public school, he is trained on spartan lines both as a servant of abstract power and a master of lesser humans; he is bred in an elite known to each other in strength and weakness from earliest years, immured to the hardships of power as well as made desirous of it; inculcated in the dominant mystique and way of leadership, and isolated from the rest of the community even at play.

To this day, the “public” school system of education dominates the British ruling class and the task of governing the nation at top level is entrusted to it. Only now has it been possible to envisage a revolt from within, since the continuous absorption of the new ruling class by the old has diluted the latter to a greater extent than was ever thought possible. The capitalist class was welded into the old aristocracy upon the playing-fields of the public schools. Now, a new liberal ruling class is rising from the managerial and technocratic ranks and sensibility and intellect may be found even among the education-fodder. A Shelley (vii) is no longer a total phenomenon in the public school or university. In any case, in modern society he would be treated rather differently. Those who aspire to a gentleman’s career in publishing do not go “Shelley baiting”, even at school. They wonder how his poetical productions could be used to advantage. Perhaps in advertising?

Even radical Dowb may be looked after nowadays; there are for him the new worlds of the film, radio, TV press and publicity. There he may enjoy progressive views if he wishes. He can combine his fashionably provocative radicalism with his innate privileges, whilst staid Dowb major pursues the more humdrum road to glory in the Foreign Office or the top echelons of industry.

The sequence of command-and-obey which is preached as high gospel in the education factories is not shattered by more generous views; indeed, the more urbane, who try to bridge the gap between the classes and are specially courteous to those who have not had their advantages may well be the more dangerous.

No longer, of course, is education itself a preserve of the wealthy or those favoured by the State. The modern State is too large a monster to be satisfied with trained servants coming from so small a minority. Not only are there wider fields for those trained to rule than ever there were, but the growth of science has created a demand for technicians and scientists. The system of licensed education in turn creates the modern fetish for examinations and the continual polishing and re-polishing of academic learning that goes with them. So we find that some pass their thirtieth birthday, still students, still about to make their contribution to society, doing their academic researches and enjoying their chosen hobbies at the expense of those who work, and the State welcomes it; for the whole purpose of education factories is not to increase the sum of knowledge, but to make docile citizens.

Kropotkin’s “typical optimism” was derided when he said[4] that a man need only work until his fortieth year, and then might devote himself to research or science or whatever took his fancy, having performed sufficient value for the community and done his share of the world’s work already. But Kropotkin was scientific enough in his analysis and assumptions, and only optimistic in that he believed scientific progress should be used for the betterment of man and not to his disadvantage. He did not believe that this would happen at all if the State were not destroyed root and branch. Because this has not been done, education remains a method of giving a little liberty within the State.

Unfortunately for the bourgeoisie, the process of education cannot be entirely canned and criticism of the present order may creep in. For some take their learning seriously and not all accept their predestined role as trainee mandarins. While the student rebellion may partly be the last outcry of nature before the obsolescence of adult professional life, it is now reasonable to expect that not every student can be bought and sold in the cattle market, and amongst the trainee mandarins there are bound to be some who will reject their destiny in the Destruction State, and it is for these that Cohn-Bendit (viii) amongst others, has become a spokesman.

It would hardly be true to assert, as do some followers of Marcuse (ix) that students form a class of their own. But, in our scientific renaissance, students cannot be charged to do nothing but think about social problems, without coming to some recognition of the basic facts of society and therefore the need for rebellion. The young automatically question established authority. Some enthusiastic Tories think that the answer to student militancy is to cut off their grants. But even the ultra-Toryism of an Abdul the Damned — to cut off their heads — would not suffice. The system will not stand up to scrutiny. The “queen of the sciences” in specific universities may still be the classical queen, theology; it may be the drag queen, economics; or the lady-president of the sciences, Marxist-Leninism in Eastern Europe — or the American equivalent, social and business administration. But now they must buy out or abdicate. The ruling class must woo and win the trainee mandarins; the current asking prices are advertised in the columns of the better Sundays. They are well in advance of thirty pieces of silver, and may even be accepted without the need for selling out. You object to using your degree for destructive nuclear research? Why not try the social services?

At present, Marx’s analysis that the ruling class is sustained by the surplus value produced by the working class, very largely holds good. We still live in a competitive society, though its edges are becoming blurred by collectivism. Labour is bought and sold like anything else. The myth of capitalism is, of course, that one gets what one deserves; those who do well out of the system like to believe that it is their superior intellect that is the cause. The Conservative credo is that without some reward, society would go flat. The same people protest indignantly when they find that “after their expensive education and training” perhaps “a dustman” is doing as well as themselves. They do not like the logical application of the competitive system which is that everything is bought and sold, and in the cheapest market possible. If there is a superfluity of doctors, down will go their wages in proportion to the national level. If nobody wants to become a dustman, the dustman’s wages will rise, unless forcibly kept down by the State. This has been a reason for government intervention in industrial matters since the Black Death caused labourers’ wages to rise, and legislation artificially lowered them.

Abolition of competition is not enough. In a non-competitive society, such as we have had in the past and are likely to have again (the Jesuit state of Paraguay or the communist countries today) the relationship of classes will still be to the benefit of those with power. Property relations have, after all, changed in the “communist” countries and classes are theoretically no more. Still, no fair observer could deny the continuation of the class system, and even those who pretend “the class struggle no longer exists” in the Soviet countries must see that while the big capitalists and landlords have vanished, and only small owners, especially small farm owners, remain (and even these face disappearance as the State extends its monopoly) yet there are quite obviously classes of some sort. Though in Russia the “capitalist” in the Marxian sense is an anachronism, and exists only on the very periphery of the economy, market trading (with illegal overtones), there is no social equality. Classes certainly exist in the sense used by sociologists to denote distinct social strata based upon different levels of income and occupation, and also in the sense of the dispossessed against the rulers, even if they no longer exist in the older sense.

In so far as this division of classes is concerned, not only is there no socialism in Russia, but the signs of it being wanted anywhere in the counties are less than ever. The working class, deceived for so long as to what socialism is and on the nature of the class struggle, uses such phrases in the way that the Christian mouths phrases without grasping their content. The Soviet under-privileged look for economic betterment individually or collectively, and lavish praise on those individual rulers who will give a little more liberty in some matters. In some of the satellites it is only necessary to do a little flag waving for the ruling class to be regarded with favour.

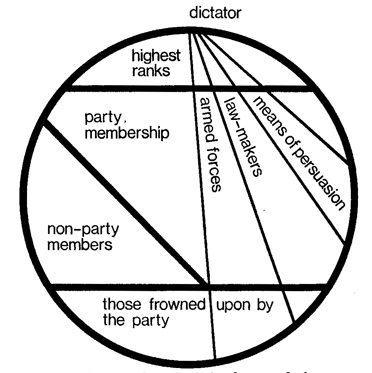

The Communist Party in these countries merely sets the tone for a careers pyramid, based upon a different set of values from those of capitalism, and yet fundamentally coming back to the lie of rewards for service; the sham need for obedience and duty; and the super-imposition of self-sacrifice when the needs of the State demand it.

It is in this respect that Russian Marxism has parted company with the Maoists, the Chinese brand of Marxist-Leninism. This wing clearly recognises the existence of class struggle both in capitalist and “communist” countries. They tend, in the capitalist countries, to be more progressive than the orthodox communists, who deny class struggle and think only of the national needs of Moscow. Although the Maoists claim to be in the tradition of Stalin, they are in fact more revolutionary than those communists who have thrown over the Stalinist myth, and as regards the Soviet Union, the Maoists proclaim revolutionary opposition much more clearly than the timorous Trotskyists were ever able or willing to do. Whereas Trotsky (x) blamed Stalin personally, or “the bureaucracy”, but insisted that Russia was “the workers’ state”, the Maoists understand there is a class struggle in Russia and its satellites, and even in China.

However, since they are themselves in power in China, it would be too much to expect them to realise that in that country the enemy of man is the means by which he is governed. They perceive the divisions in their regime, but conclude that it is due to their own shortcomings as a bureaucracy, and preach self-criticism to the point where it becomes absurd. They strive to eliminate “bourgeois relics” in their own party, thinking that by a “cultural revolution” they will be able to reconstruct the party and shake off the bad habits it no doubt acquired during the struggle against capitalism. They fail to see that what oppresses the masses is not so much the habits the party acquired under capitalism, bad as they may be, but the powers they have acquired since. They cannot introduce an anti-authoritarian regime except by abolishing themselves, and though this may be the theory of Marxism, it will never be the practice, for power readily convinces its possessors of their own indispensability.

They are revolutionary in every country but their own, like the Victorian bourgeoisie. They represent socialism without liberty — which in Bakunin’s formula, means tyranny, just as liberty without socialism means exploitation.

With this “liberty” without socialism we in the West are familiar. It is seen in the plea of the private-enterprise capitalist to be left alone by the State to make money and keep it. But he does not entirely reject the State; he merely despises it, as the public hangman was once despised and rejected by the supporters of capital punishment. If anything is run by the government it cannot be any good, he says, but he calls for greater punishment by government of those who interfere with his profit-making and safety. At the height of his individualism, in the middle of his boasts as to the manner in which he left his former employment to start on his own “to better himself” and never looked back (or beneath) he wants the government to take legal sanctions against those who leave his own factory gates to go on strike to better their own lot.

This “liberty”, too, is the “national” form which consists in the right to have the same tongue as the otherwise faceless rulers. It is the “liberty” one defends when one has surrendered every civil liberty to become a soldier. It is the classical “liberty” to starve on a park bench or to dine at the Ritz, modified today by the fact that the State will readily take charge of the vagrant and so enable the expense-account diner to sup at the Ritz with a comfortable conscience.

It is the “liberty” to say whatever one chooses, within reason (that is to say, within law) provided one does nothing effective about it. Cant about liberty may always be recognised; it is accompanied by a hope that liberty will not become “licence”, that is to say, that it will never be real freedom, and that nobody will take advantage of benefits really intended for those conferring them. It is “liberty” for politicians to criticize each other, and a breach of privilege for us to criticize them when they do not feel like it. It is “liberty” for judges and magistrates to express their prejudices, it is “contempt” for us to reveal our contempt.

Law is not liberty. The most progressive laws merely mark the boundaries beyond which liberty may not go. To express social change in terms of law means a defeat in the class struggle, not a victory; it facilitates the rise of a new ruling class, or renders the old one more capable of withstanding supercession.

All classes may be revolutionary. All are capable of making great changes and reforms. All may, in their time, be progressive, and degenerate only with changing conditions. But only productive classes can be libertarian, because they do not need to exploit others, and do not need, therefore, to maintain either the machinery of exploitation, or the means by which others can be forced or persuaded to give up their liberty in return for real or imagined protection.

2 The Road to Utopia

We can hardly declare ourselves unconditionally for unbridled freedom and then go on to lay down blueprints for the future. We are not clairvoyants to be able to predict the social and economic structure of a free society. It is not possible to lay down rules as to how affairs should be managed when the management of mankind itself is abolished. But at the same time, the rebel in this society cannot be patient enough to wait for an expression of spontaneity as if for the Messiah. He has to choose a programme of action and the road to Utopia. There may be more than one way, and we may need to shift our course, but the knowledge of where we want to get enables us to pursue a consistent course at the moment.

If our aim is the abolition of the State, it does not make good sense to think of forming a new state when the capitalist state is abolished, still less to establish a dictatorship. This, of course, was a fallacy of Lenin’s (xi), whose programme of action was geared up to the circumstances of the First World War (and not to Utopia), and whose theoretical conclusions were bound up with the conquest of power by his party. He sought to justify this in socialistic terms. The “soviets”, workers’ and soldiers’ councils, and the local communities of peasants, were already in control when the Bolsheviks (xii) returned to Russia. He retained the name, but in practice applied it so loosely that today the term “soviet” is little more than a synonym for the Russian Empire.

Lenin advocated the “withering-away of the state”, in Marxist traditional language, though to an extent which surprised contemporary Marxists in the social-democratic movement (who felt he was “trying to steal Bakunin’s thunder”). He pursued an entirely different road to one which would lead to the end of government. He strengthened the repressive force of government and abolished only those organs of the state which existed exclusively to enforce the competitive system. By doing this he was ultimately working to the same goal that other Marxist social-democrats had in mind, and may have been wiser in his generation than they. German Marxism would have led to the same reality as Russian Bolshevism, perhaps in a less brutal fashion, perhaps not. Both diverged from the class struggle. They aimed at re-imposing the rule of one superior section of the community upon another, and replacing party rule for the old rule. The party in Russia became a bureaucracy and the bureaucracy became a new ruling-class. In the sense that it works for wages and not for profit, it is not a capitalist class, but it is a higher social class and could hardly be called a productive one.

Many of those who opt out of the class struggle, or frankly change sides, do so because they see only too clearly the grimness of state communism, in which the State is all and the community nothing. But the fact that it suits Russian and Chinese imperialism to claim that the interests of their respective governments are parallel with those of the international class struggle, does not make them so, any more than the claims of the American and British governments to represent democracy need be regarded seriously. Without the idea of what the struggle is about, without the vision of Utopia, the struggle is lost.

Few can do without the vision of Utopia. It is true the vision varies. It was a German militarist who felt that universal peace was “a dream, and not even a good dream”, and the militaristic Utopia was for him typified by Valhalla. The authoritarian pictures his ideal society as one in which he has only to breathe a command, and the world jumps to its feet to obey. Unfortunately, this is not entirely a dream. It is true that, so far as their personal ambitions are concerned, most authoritarians recognise it as a fantasy. But though diey may never hope to achieve complete authority themselves, they work towards an authoritarian ideal. In this pursuit they may support tougher prison sentences or the reform of prisons (the second is only the more tolerant version of the first). They may advocate corporal punishment or the death penalty, or according to their political opinions, support nationalisation of industry or strong central government. All are aspects of authoritarianism falling short of the complete state-fantasy. Naturally, according to more or less liberal opinions, the authoritarian may differ on these concepts, so that those who want one conclusion do not necessarily want the other.

Some professional people, who predominate as Labour MPs, see their Utopia as the welfare state; a glorified housing committee run by experts and modified by advice bureaux, with themselves as wise and kindly fathers of the people. Meanwhile they settle for reforms in this direction, some of which may be good, but they all lead to Big Brother. Oh the other hand — very much on the other hand — there are those who see the nation reformed in the manner of Craft’s Dog Show, as a racial Utopia; meanwhile they settle for nagging immigrants about their degree of sun-tan. Other authoritarians may have the vision of that Czar who drilled his soldiers to perfection and then had but one complaint: they still breathed.

Those who reject authoritarianism will require nobody’s permission to breathe. The libertarian owes no duties or allegiance; is not grateful for permission to reside anywhere on his own planet and denies the right of any one to screen off bits of it for their own use or rule.

The libertarian rejection of all authority may amuse or terrify the shepherd, according to the degree of self-confidence or the militancy with which it is put forward: it invariably provokes consternation among the sheep. What would life be like without the shepherd? they bleat, their dismay heightened even more by the fact that they hate and detest the shepherd, whom they know ultimately intends to slaughter them. But the startling supposition that they could exist without him implies that generations of mutton-yielding were in vain.

Objections to a free society, one without repressive institutions, come even from those who pay lip-service to the idea that the state itself is an evil, even if thought of as a necessary one. They have similar underlying assumptions, the most frequent of which is that there is no alternative to coercion of one sort or another, and that all social problems must be solved by compulsion — either legal sanctions or economic pressures. “Who will do the dirty work?” they demand of the anarchist, implying that either some must be starved in order to do what they regard as uncongenial; or else that the government must force people to do it (on the lines of war-time direction into the mines, or military conscription). Although this argument is intended to demonstrate the alleged impossibility of freedom, it is equally a criticism of any form of general prosperity. It is why outspoken Tories (those with safe electoral seats in areas where support for unemployment as a policy will not be unpopular) demand a margin of worklessness. Society finds it difficult to answer the question as to who will do uncongenial jobs if there is neither industrial conscription nor the spur of starvation. At present, the democratic state postpones the problem by a shuffling around of populations causing the less popular work to be done by the more recently arrived people.

Another assumption is that there is no logical alternative to government but lunacy, and this is even held when, as has not infrequently been the case, the government is in the hands of raging lunatics anyway. It is believed that society would, in the absence of government, allow any maniac to dominate and kill, or persuade people to do so to each other, and all that prevents this is the restraining hand of an institutionalised legal system. But to see that this is a fallacy, one need only read the crime news. It is the legal system itself which allows maniacs to dominate and kill, collectively or individually, as part of command-and-obey, and which allows them to get into positions where they can either act in defiance of other people’s law or alternatively where they can fashion the law for themselves.

When an anarchist position is placed before those who have never previously questioned authority as such, they show the fear of the modern jungle which normally they sublimate. Like the fictional pygmy people of the forest, they look to Tarzan to protect them from the terrors of the jungle, however much they may normally criticise their governmental Tarzan. Take away Boss-Tarzan and they see themselves isolated in the jungle. They do not comprehend that there can be a jungle pruned, cultivated, civilised; a situation in which Tarzan is unnecessary for their protection, and in which it becomes clear he is only there to exploit their labour.

“Thieves and maniacs would beset us!” cry the supporters of government. “Our wives would be raped, our property taken, we would be murdered!” But all that happens to them in the jungle, despite Tarzan, often through his connivance, and sometimes directly by him. It does not happen in the cultivated garden of which they have no experience. In the jungle in which we live, murder is recognised as such only by virtue of whether it has been legalised or not, and the primary motive of the ambitious is self-aggrandisement at the cost of others. When the ambitious have power, they preach self-sacrifice by others. (Be “restrained”, be patriotic, have the “national” interest at heart). Of those who sacrifice, it can only be said they lose out in this system. For the only means of independence in the jungle is by the possession of property, by cornering a portion of the community and using it for personal ransom. Proudhon (xiii) was not in the least guilty of a contradiction, as some pedants think, when he said that property was theft but that it was also liberty. It is like a gun, useful in the jungle and the only means of preserving independence within it, but nevertheless anti-social the moment a society escapes from the jungle.

The free society cannot know anything of special property rights any more than it can of privilege, hereditary or acquired, for special liberties for some imply less for others, and competition for betterment at the expense of others can only be settled by force. The necessity for the system of ownership of property at present is in order to corner the market in necessities and to hold the community to ransom. The community, being the greater, will not be held to ransom unless some repressive machinery (force or persuasion) makes it do so.

By co-operative production the natural wealth of the world can be available to all. This would only be a mixed blessing if government still existed. The inevitable tendency of government is to create special privileges for itself and so re-establish inequities. Where would the delights of public life be without the serfs marching past to salute; or the flag-bedecked limousines, or the dignified jaunts at the public expense? The government, being itself by nature a privileged class, must introduce — if these ever went — the system of rewards and incentives that persuade others of the necessity and the joys of obedience. This is exactly what has happened in Russia, but is paralleled in the Western countries, too. The measure of independence is that one does not need others to grant one rewards or allow one incentives. These are given to inferiors. What small shopkeeper today, for instance — without some ingenious tax fiddle, at least — would gravely allow himself an overtime bonus of a pound a week, to be deducted from his own profit? It would be equally absurd for the worker if he controlled his own factory.

Free co-operation naturally leads to decentralisation, and possibly the ending of a lot of large-scale production which is the joy and pride of monopoly, whether capitalistic state or even co-operative. The craftsman nourishes in a free society, when the building of pyramids or vast office blocks falls into disuse.

Workers’ control is a question of economic freedom. It has nothing in itself to do with morality or ethics, which are quite different problems. The old conservative criticism, that men must be angels before they will work together like men, is echoed in the plea of the Christian Socialist for moral perfection before Utopia is possible. Here is Charles Kingsley’s address to the Chartists:

“You have more friends than you think for . .. you may disbelieve them, insult them — you cannot stop them working for you, beseeching you as you love yourselves, to turn back from the precipice of riot, which ends in the gulf of universal distrust, agitation, stagnation, starvation ... will the Charter make you free? Will it free you from slavery to ten-pound bribes? Slavery to beer and gin? Slavery to every spouter .. . ? That I guess is real slavery, to be a slave * to one’s own stomach, one’s own pocket, one’s own temper. Will the Charter cure that? Friends, you want more than Acts of Parliament can give ... there can be no true freedom without virtue ... be wise and you must be free, for you will be fit to be free.”

There is no doubt much good sense in all this, but it is insufferably patronising, and is untrue as far as the particular aims of the Chartists were concerned. For the middle classes were free enough within the limits of what the Charter demanded, though they were slaves enough to their stomachs, pockets, tempers and spouters. Far more so, one might have thought, than the Victorian working-classes. From Kingsley’s approach, rejected by the materialist socialist, sprang the common modern fallacy that revolutionary socialism is an “idealisation” of the workers and that the mere recital of their present faults is a refutation of the class-struggle which (it is again supposed) can only exist if a Kingsleyan idealised proletariat can be proved to exist. Poor Kingsley! His dictum that “religion is the opium of the people”, quoted by Marx and usually attributed to Lenin, has also been generally misunderstood. Opium was then used in operations when the pain was too unbearable, since anaesthetics were unknown, and evangelical religion was also resorted to when existence became otherwise unbearable.

This attitude has passed over as an inheritance to the peace-movement liberal, who finds himself in the libertarian camp for purely political reasons (disillusion with politics or a recognition that “war is the health of the state”). To the Christian Socialist or his secular equivalent it seems morally unreasonable that a free society, still thought of in terms of “reward” or “privilege” could exist without moral or ethical perfection. But so far as the overthrow of society is concerned, we may ignore the fact of people’s shortcomings and prejudices, so long as they do not become institutionalised. One may view without concern the fact that bothers the advanced liberal; that the workers might achieve control of their places of work long before they had acquired the social graces of the ‘intellectual’ or shed all the prejudices of the present society from family discipline to xenophobia. What does it matter, so long as they can run industry without masters? Prejudices wither in freedom and only flourish while the social climate is favourable to them. The Israeli kibbutzim are an example of people working in free conditions, despite advanced patriotic or religious prejudices which make them far from libertarian in their relationships to people outside. What we say is, however, that once life can continue without imposed authority from above, and imposed authority cannot survive the withdrawal of labour from its service, the prejudices of authoritarianism will disappear. There is no cure for them other than the free process of education, and the disappearance of rule-by-persuasion.

Free education has already progressed in this direction. The pioneering work of A. S. Neill (xiv) which was nurtured in private schools for a very small minority, went on to influence a whole generation of teachers. But however much progressive views on education are important from the point of view of a child’s happiness, and even today help to alleviate the bigotries and hatreds of school life, they can only ultimately enable the pupil to integrate into present-day society.

Today, an increasing number of teachers and pupils recognise that this is not enough. Allied to free education must be the movement to alter society. It is not enough to abolish examinations, one has to alter a competitive society. It is not enough to abolish classroom dictatorship, it is necessary to abolish governmental discipline. From the Neill movement has grown the movement of pupils, from classroom alliances to student associations, which understands that education has always been subservient to the ruling economy, and which is not content only to make the paths of education more pleasant but also wants to make its education applicable to life in a free society.

Least of all does it concern itself with the facts of discipline or otherwise, with which the do-gooders feel it should be solely concerned. It is not solely a question of standing up against intolerant teachers, or tolerant ones with jobs to consider, but tolerance and intolerance are only different sides of the coin of authoritarianism. Nobody in his senses says that he has an objection, or that he does not have any objection, to Scotsmen coming to Great Britain. It would be idiotic, for the question of tolerance and intolerance does not arise; they are there as a right.

To the libertarian, the world in his own. Those who have superior force may, according to nature, be kindly and generous or despotic and illiberal, but they are our enemies. Though naturally most people prefer to have a more generous enemy in the saddle, they survive the longest. The growth of fascism made the situation more complicated. The despotic and illiberal became so dominant, and the generous so rare, that the latter seemed like a port in the storm. But with all their tolerance, the liberals will, in a crisis, betray their posts, for in times of stress they see “the floodgates of anarchy” opening. History has shown how the liberal will call in the army when things get tough, knowing that it will cause the downfall of democracy, but preferring that to revolution. General Franco was a paid Army officer on the salary list of the Republican Government he destroyed. The “impractical” Anarchist movement, the CNT-FAI (xv) called for the abolition of the Army and fought against it. The socialists and republicans preferred to bring in “reliable” Army officers, such as General Franco, with his Masonic background, replacing the monarchist officers. The Republic felt that this would save them from both fascism and the workers. The result is well-known.

In a like manner, faced with the possibility of a postwar revolution all over Eastern Europe, once the Nazis had been defeated, Mr. Churchill and Mr. Roosevelt preferred to sell the lot out to Soviet Russia, “the devil they knew” to which they had always been implacably opposed, rather than the devil of social revolution they did not know but feared all the more. Anything was better than the “floodgates of anarchy” so far as they were concerned. So far as we are concerned, these are the gates which have to be opened.

3 The Labour Movement

Anarchism as a movement in its own right has its own traditions, now a century old, yet forms a faction within the international labour movement as a whole. It has its particular inheritance, part of which it shares with socialism, giving it a family resemblance to certain of its enemies. Another part of its inheritance it shares with liberalism, making it, at birth, kissing-cousins with American-type radical individualism, a large part of which has married out of the family into the Right Wing and is no longer on speaking terms.

To understand Anarchism, it is necessary to understand the parting of the ways in the labour movement, by which term is not implied the Labour-TUC-Co-operative set-up; though this is also part of it, and happens in Great Britain to be the dominant tendency.

The anarchist tradition has its own martyrology, sometimes shared. There are the Chicago Martyrs (xvi); Sacco and Vanzetti (xvii); Joe Hill of the IWW (xviii); and a roll-call of heroes as well as a record of successes and failures. But if it is unsatisfactory, except by way of inspiration, to judge a movement by the spontaneous devotion it inspires (which can be said of many evangelical sects, though noticeably lacking in the established parties and religions of today), it is equally so to consider a movement, not based on rigid party lines, merely on the basis of the success and failures of those who happen to be its current adherents. To gauge “the anarchists” in terms of somebody who happened to do something or other at any particular date, is to affirm the obvious, that in the absence of rigid party lines, to conceive a movement too broadly means one will include not only its heroes but those who may not necessarily measure up to its tenets. This is inevitable if one rejects, even assuming it were feasible, the ideal of legal copyright in a name.

Fortunately, a certain shock-therapeutic value in the connotation of “anarchist” with “terrorist” has preserved it, by and large, from becoming as debased as the once great names of “radical”, “socialist”, “liberal”, “communist”. Only when a faint tinge of radicalism is acceptable does the liberal, advanced in ideas but indisposed to action, care to make use of the name, and then usually qualified with a hyphenated dilutive (anarchist-pacifist, philosophic-anarchist, anarchist-individualist) that does not jar too much in the literary, artistic or academic world. The diluted-anarchist is more absent among the scientific intelligentsia where profession of belief would require a stand to be made. An artist, on the other hand, might be forgiven the use of the name — it might even be expected of him. He can hang his pictures in the Royal Academy and even paint the Queen (as did the late Augustus John) without disguising his opinions. It would be a bold scientist who stated his dissent while working among the Establishment.

It has been cynically observed that, despite the wealth of the anarchist tradition, every young generation that finds the way to anarchism for itself, and not by way of introduction from others, falls into the delusion of being the first to discover it. By extension the hippies believe they were the first ever to drop out of society. This Columbian delusion is harmless enough, except historically; to it the generation of the sixties, or at least its outside interpreters, has faithfully adhered. Dutschke (xix) has re-stated, and the discovery re-echoed around the militant world, the case for council communism, often distorted today by Maoist or Ho Chi Minhite phrases which express a confusion of thought in opposition phraseology. It is also sometimes referred to as “anarcho-Marxism”, as if this were a modem amalgam resolving ancient antagonisms. Again this is misleading, as anarcho-syndicalists (anarchists within the labour movement) always accepted Marx’s economic criticisms and analysis and disagreed with Marxism only on the need for legalism, political leadership, the question of State control or the role of the party. All this is exactly what is accepted by “anarcho-Marxists”, like Cohn-Bendit, from the anarchist tradition.

It is true, however, to say that the Marxist tradition in the working class, at the point which it reached among the Spartacists (xx), for instance, becomes indistinguishable, except in phrases or associations, from anarcho-syndicalism. It may, when deriving from a more genuine proletarian tradition in particular countries, be more revolutionary than an anarchism still identified, at too late a period, with the trade union type of organisation, or divorced from the struggle as an ideological union and nothing more.

The tradition of working-class association stems from the guilds of craftsmen in the Middle Ages and was developed in the struggle against industrial capitalism. Trade unionism was obviously the first step forward in the Industrial Revolution, as a means of defence, and of representing the organised workers against their immediate oppressors. The fact that, in the type of trade unionism of which the TUC is now a model, there was an institutionalised or parliamentarian leadership, did not prevent economic advances being made. Many of the trade union pioneers, including some who later became reactionary, were socially progressive for a period. Local militancy was always able to keep trade unionism an effective force whatever the leadership, but the First World War brought the first major showdown. Until then it was of less importance that the leadership was reformist than that union solidarity should grow, unless the leadership positively inhibited the growth of the union. This, for instance, happened in the American labour movement, which, by its insistence on craft unionism, originally adapted to the facts of the ‘seventies and ‘eighties, became by the turn of the century so divisive as to be powerless.

The British trade union leadership, influenced by the Fabians (xxi), generally depended upon legislation rather than direct action to bolster up their effectiveness. They turned first to the radical wing of the Liberal Party, and then to their own candidates, who later linked with the social-democratic movement to form their own Labour Party. The American trade unions, on the other hand, lacking both Fabian and revolutionary influence, left the social-democratic movement to its fate as a sectarian party that waxed and waned to a shade. They had a distaste for politics as recognisably corrupt and turned to bargaining with the employers on a purely commercial basis. This naturally brought into being, as well as the giant company-type unionism of today, also the gangster-controlled union (crime is after all a business like any other) which competes for favour in the goods it can deliver, with the “clean” union that sells its rule-book for cash gains and whose bosses set their salaries according to their “opposite numbers” in industry.

With the boom expansion of American capitalism, in a period of uninhibited technological advance, and with the rest of the world reduced by war, the American worker has thus become the highest paid and least powerful in the world. Remembering his helplessness in time of depression, he is all the more inclined to conform during the period when his helplessness is at least paying off in high wages and good living. Those who artificially produced the slump have now artificially produced prosperity. His attitude is that of Napoleon’s mother to the First Empire — “It’s all right, as long as it lasts.”

In France the trade union movement grew up in quite a different atmosphere. At the turn of the century anarchism was at least as popular as state socialism among the French workers. The anti-political theory competing with the parliamentarian for influence, it was natural that in a period of struggle the former should come more to the fore, though acknowledgements must be made to the work of Pelloutier (xxii) in the CGT. The labour movement wished to achieve independence from the State, and set as its task not merely the economic betterment of the workers by direct action, but also the control of each industry by those working in that industry. The French word for trade unionism, syndicalism, became synonymous internationally with that form of labour organisation which abjured parliamentarism and set up workers’ control as the road to Utopia.

The French workers had perfected the strike weapon and all forms of industrial struggle, including the occupation of the factories — to which, years later, in 1936 and again in 1968, they returned, long after parliamentarism had appeared to prevail. It was their view that the social general strike would be no more than an occupation of the factories, after which the workers would resume work but keep the employers and the State locked out. This becomes more than occupation. It is expropriation: the final challenge to capitalism.

In Italy, such an occupation of the factories in the ‘twenties was answered by the bourgeoisie, although disposed to liberalism, turning in despair to fascism to rescue the capitalist system from expropriation. The current phrase is “right-wing backlash”. In Spain, where social-democracy was a latecomer, the labour movement was mostly anarchist, and the workers responded to what was intended as an army takeover to prevent social expropriation, by the greatest force at their disposal, the social revolution itself. The ruling class retorted with the greatest force at its disposal, genocide. The original Dollfuss-type fascism became civil war by the ruling class against its own people, which is the class struggle in its crudest form.

In the United States there was a reaction to narrow craft unionism when the Industrial Workers of the World (xxiii) was created. It was influenced by French syndicalism, possibly at second hand, by Italian immigration, by native American radicalism, by East European anarchism and to a small though perceptible extent, by the theories of Daniel De Leon (xxiv). It was part of the syndicalist development throughout the world that influenced American, Australian and some British thought on the need for worker’s control within the socialist society. It showed how the new society should be “created within the shell of the old” by industrial unionism. This prototype of revolutionary labour thinking was in direct contrast to the parliamentarian labour idea current in the British trade unions which had created the Labour Party. Fabian influence, which had pushed them in the direction of the Liberal Party, re-created the image of the latter in the new party.

The role of the trade union leadership in bargaining directly with capitalism and using working-class militancy, or at least the threat of it, as a lever, has nowadays been challenged by social-democratic politicians who want to make the unions into bargaining agencies of the State. This trend first emerged in the First World War, when the alleged national exigencies gave the government the chance to curb the labour movement. Only the militancy reintroduced by the short-lived British syndicalist movement and the IWW saved the working class from a complete collapse into industrial serfdom, from which the declaration of peace would not necessarily have saved them.

In that war, those who had always applauded the value of a free market and the ability of unfettered enterprise to deliver the goods, and indeed still let the manufacturer go on making profits in order not to interfere with the sacred rights of property, were quite adamant that the working class had to sacrifice if the nation were to be triumphant. The parliamentarian leadership of the unions immediately capitulated. In Britain it collaborated, in Germany it obeyed. In both countries it began the long, disastrous course of accepting State intervention in industrial affairs.

In Britain this was the logical consequence of Fabian influence. In Germany the socialists had denied there were any great possibilities in the union movement anyway. Lassalle (xxv) had formulated his Iron Law of Wages, popular again nowadays among the economists, by which it alleged that if wages went up, so did prices, and all union activity was a vicious circle.

As a result, the trade union movement in both countries was held to be useless to its membership, so far as any prospect of defending their living standards was concerned. All strikes became “unofficial” — a curious phrase, suggestive of an alternative possibility of licensed rebellion. When the workers turned to the trade union movement, for defence of their living standards, they found it was incorporated in the State. But in every factory, the shop steward, who had up till then been a collector of dues from the worker on behalf of the trade union, and no more (though this in itself, during an anti-union period, had been a job requiring guts and militancy) became responsible for industrial liaison. Unlike the trade union official, away from the job, elected to office by people who did not know him or by a minority consisting of regular attenders at branch meetings, usually the politically committed, and by now as remote from his former workmates as the factory inspector, the shop steward was directly responsible to the men on the shop floor.

It was automatic that decisions had to be referred to each mass meeting, and the shop steward had to follow general decisions or resign his post. To the press, always seeking for “leaders” in order to personalise news stories, he was the “trouble-maker”. So he was to the police, seeking a few scapegoats “in order to encourage the others”. But the truth was that in an atmosphere of independence and conscious militancy, such as already existed on Clydeside and which later spread — both here and in Germany — he was only the mouthpiece for the whole body of “trouble-makers”. That is not to say that in some places, where there was a “committed” minority, the more persuasive speakers did not become shop stewards and effectual leaders of the movement. Ultimately, under the influence of the Russian Revolution, this happened almost everywhere. Leadership is sometimes inevitable, and something to which, in default of independent action, the libertarian revolutionary must be drawn or must abdicate action.

To speak of leadership is not necessarily to speak in authoritarian terms. It reflects not on the leaders so much as on the lack of spirit of the led. Free men need no leaders. Leadership may happen in default of spontaneity. It may be necessary to wake people up. It is still a fact that it affords too many temptations for the leadership to exercise authority and for it to step from delegatory mandatory office to making decisions for others. The quality of leadership at different periods is often criticised. What is wrong is the fact of leadership, and more particularly, the necessity of it.

The linking-up of the shop-steward movement was firstly on the basis of mandating delegates, subject to recall. Only later did some of the more militant of these pass upwards into the role of leaders. The movement spread from factory to factory in British industry during the First World War. It began in the Scottish heavy industries and finally engulfed production,[5] despite the eloquent appeals of Lloyd George and his kept union officials. The proudest banner it had was the principle of workers’ control, introduced by pre-war syndicalism, and in the course of its strategy it showed how workers’ control could be achieved.